The Imitation Game: Cosmetic Edition

.jpg)

Background

Now more than ever, Australia’s consumer brands are assuming bolder and more direct marketing strategies in an effort to outmanoeuvre their competitors. Capitalising on another brand’s reputation has become far more common in Australia, although the financial and reputational costs of getting it wrong can be substantial.

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, a “dupe” is a term “…used to refer to a product made to look like a more expensive or high-quality product.”

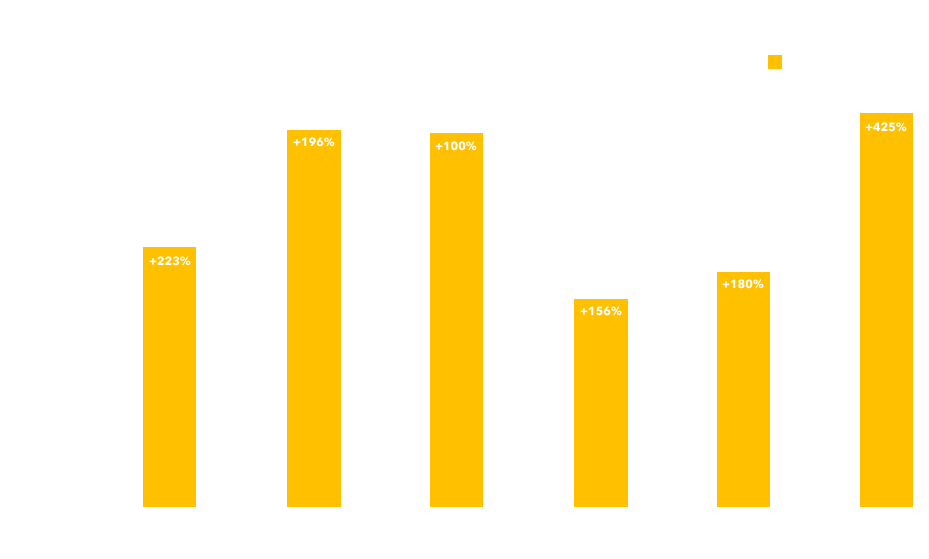

Data from Barefaced, a leading Australian beauty market research firm, reveals the rapid and undeniable surge of dupe culture across major global beauty markets:

Source: Barefaced Substack

This phenomenon can partly be explained by a perfect storm of circumstances: the virality of social media trends, luxury-obsessed Gen Z and Millennial consumers and mounting cost pressures. Where knockoffs may have once been considered tacky, for today’s younger customers, there is cultural cachet in choosing dupes over the real product.

To explore this burgeoning practice, our Legal & Regulatory team will be analysing a series of domestic and foreign dupes and the legal considerations involved from a strictly Australian context.

The Billion Dollar Playbook

The success of MCo Beauty (MCo) serves as a perfect case study for how lucrative a dupe strategy can be when executed with precision. By strategically navigating IP laws, MCo experienced explosive growth, scaling from $10 million in FY20 revenue to a projected $330 million in FY25, a staggering CAGR of 101%.This remarkable trajectory culminated in February this year, when Founder andCEO, Shelley Sullivan, sold her remaining 50% stake in MCo to Dennis Bastas’ DBG Group, securing a billion dollar valuation that transformed her into one ofAustralia’s most successful beauty entrepreneurs.

Examples of MCo product dupes and their original counterparts are noted below for reference:

Source: Barefaced Substack

MCo's rampant growth can be credited to a distribution strategy that capitalises on high-traffic retail channels such as Coles, Woolworths and Chemist Warehouse.Securing extensive product placement across mainstream grocery and pharmacy networks, coupled with the use of targeted retail media (i.e., Cartology) and influencer-led marketing, has empowered MCo to achieve mass market penetration and drive sales.

An incremental benefit of this approach is that it probably also helps to guard against potential IP infringement. By stocking its products in budget-friendly retail environments, MCo appears to be relying on the supposition that customers would not expect to find luxury products in those settings and as a consequence, they would not be confused by MCo’s dupes.

The Sweet Smell of Success

Part1 of this series features Whif, the Australian fragrance disruptor taking on luxury giants. The digital native brand offers premium, sustainable and cruelty-free scents “inspired by” iconic, designer perfumes from the likes of Dior, Chanel and Le Labo, all for a fraction of the cost.

Through compelling and authentic storytelling via social media channels, Whif has swiftly captured the hearts of Gen Z and Millennial consumers alike. It’s strategic adoption of the imitation model has enabled it to democratise luxury fragrances, breaking down traditional barriers while delivering accessible luxury to a mainstream audience.

Still, it remains to be seen whether Whif’s rapid ascent will invite unwelcome legal scrutiny from established luxury houses. We delve a little deeper below:

Trade Marks

A registered trade mark provides an owner with exclusive rights to use the mark within its registered class. Section 120 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (TM Act) prohibits another person from using a sign as a trade mark that is substantially identical or deceptively similar to the registered mark. In the context of dupes, where an imitation brand uses another brand’s registered mark, the question of whether that mark is being used ‘as a trade mark’ is of critical importance because if not, the use will not contravene section120 of the TM Act.

In2023, the High Court in Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd v Allergan Australia Pty Ltd grappled with this very question in a landmark decision. In that case, Self Care had developed an alternative to Allergan’s Botox product, using the words "instant Botox® alternative" on its product packaging and website. The court held that this did not amount to use ‘asa trade mark’, including because those words were:

- a descriptive phrase with an ordinary meaning;

- intended to differentiate the product from Botox (i.e., as an ‘alternative’);

- displayed beside Self Care’s actual brand, “freeze frame” and “INHIBOX” (themselves used in a branding function) which were dominantly displayed; and

- used in various ways in plain font, in inconsistent styles and sizes.

Analysis

Like Self Care, Whif has been referencing other fragrance brands (some which are the subject of trade mark registrations) and in doing so, has advertised its products as being “inspired by” those fragrances.

The Whif products conspicuously display the Whif branding and accompanying product name (i.e., Sable Journey, Moonlit Desire and Jasmine Euphoria). Given the stylised font (including the consistency in ‘Whif’) and prominence of the words, these inclusions appear to perform the branding function, or ‘useas a trade mark’ function, as described above.

Further, the reference to Whif’s products being “inspired by” certain other fragrances (i.e., Luis Vuitton’s Ombre Nomade, Chanel’s CocoNoir and Christian Dior’s Dior J’Adore) that appear on its website provide the descriptive and differentiating language referred to in SelfCare. That is, they describe the products and differentiate its origin from the other fragrances. The references are intentionally in plain and ordinary style and displayed against Whif’s actual dominant branding and accompanying product names.

Given these contextual matters, despite referring to other fragrances which are each subject of a trade mark, the use of those trade marks by Whif in connection with its own products does not appear to be use ‘as a trade mark’.

Misleading and Deceptive Conduct

Misleading and deceptive conduct under the Australian Consumer Law casts a wider net than theTM Act. Even when a brand isn't used ‘as a trade mark’, brands can stillface liability if their conduct misleads consumers. This may be wrongfully conveying product connections, affiliations or capabilities. This provision focuses on protecting consumers from being led into error.

InSelf Care, one of the allegations was that consumers were misled into believing that Self Care’s ‘INHIBOX’/‘FREEZEFRAME’ product would have long-term effects like Botox. That claim failed. The court found that consumers of the product would understand that the lower cost and topical nature of the product did not convey that it would function like a product applied via a medical practitioner. This is somewhat analogous to Whif, which is promoted as a lower cost alternative to luxury fragrances and is differentiated by the words “inspired by”.

If a claim were brought against Whif, it may be a defence that to the extent their product was not of the same quality as its corresponding luxury fragrance, consumers would not be misled because a reasonable consumer would not expect the product to have the same characteristics as a luxury brand.

Playing the Imitation Game: A Survival Guide

To reduce the risks of misusing other brands:

- First, an imitation ‘brand’ should be prominent and distinctive (e.g., ‘Whif’). A reference to another brand should not be presented as a badge of origin.References should serve as comparisons or descriptions; not suggestive that the product originates from, or is affiliated with, the referenced brand.

- Second, consider the consumer perspective carefully. Examine how customers might interpret the packaging, advertising or product descriptions, paying particular attention to the relative prominence of different elements.

- Third, include clear disclaimers when appropriate. Unambiguous statements clarifying the lack of affiliation between brands can provide important legal protection, but these should be prominently displayed rather than buried in fine print.

- Finally, ensure all claims are accurate and supportable. Any representations about product performance, quality or characteristics should be backed by solid evidence and avoid creating unrealistic consumer expectations.

This article is general legal analysis and does not constitute specific legal advice. Brands should consult qualified legal professionals for guidance on their particular circumstances.